How dangerous the different energy sources actually are? Evaluating the problems of different energy sources is always wrought with controversy, as there is not and can not be a single, universally acceptable method of evaluating the severity of what may be very different impacts. For example, how one should evaluate health effects on children compared to elderly, or health effects on humans to damages to environment?

Nevertheless, some commendable attempts at comparing the dangers of energy technologies have been made. Among the more recent ones is a study commissioned by the European Union and performed by consulting company Ecofys. Known for its pro-renewable and anti-nuclear reports, Ecofys estimated the average so-called “external” costs of different electricity generation technologies in use within the EU. In this context, external costs refer to costs the energy generators do not have to pay, but instead “externalise” to the society as a whole.

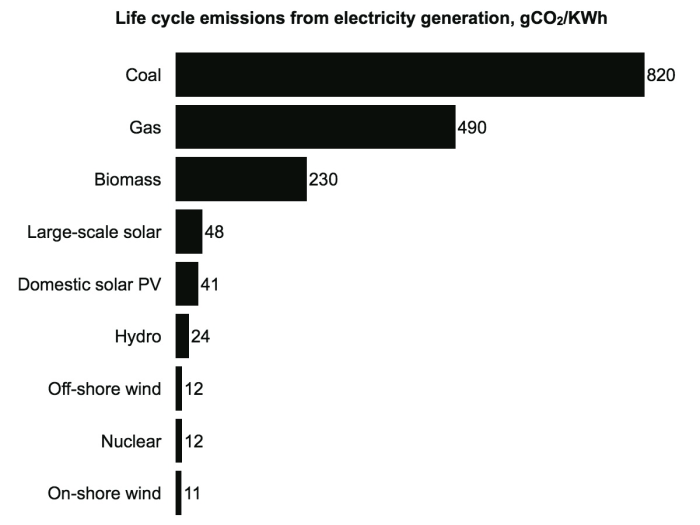

The Ecofys study referenced here is not without its problems, but it nevertheless remains an admirable effort at evaluating the dangers of different energy sources on a level playing field. As we can see from the results, even the highest estimate for the dangers and costs of nuclear power comes below the costs of natural gas, and comfortably close to the costs of biomass use – whose radical expansion is one of the keystones of every non-nuclear energy scenario presented by traditional environmental organisations.

The low estimate, on the other hand, comes well below the impacts of solar power. That’s even when the impact of nuclear accidents is factored in.

If we take the Ecofys study at face value, we should probably conclude that the dangers of nuclear energy are on par with dangers associated with most forms of renewable energy. The dangers may be different, of course: renewable energy sources do not experience meltdowns, but they may emit considerable pollution during their construction or use. The end results, however, are similar: both acute and chronic illnesses to people exposed.

It should be noted that the findings of this Ecofys study are in line with findings of a review commissioned by Friends of the Earth UK: in the review of relevant scientific literature, the report concluded that

“Overall the safety risks associated with nuclear power appear to be more in line with lifecycle impacts from renewable energy technologies, and significantly lower than for coal and natural gas per MWh of supplied energy.”